Take this scenario…

I’m calling my mobile phone provider to get an upgrade on my (recently smashed) mobile phone. I’m innately aware that I want something from this person: an upgrade with the fee discounted, and my loyalty discount retained, and with a few extra gig memory for good measure.

I cannot do this without Gerald’s (lets call him Gerald for ease) support. Therefore I am dependent on Gerald. I find myself being super polite to Gerald, even though Gerald is quite unhelpful. I would really like to tell Gerald he is being quite unhelpful, and rude, but my needy self is being oh-so-understanding because I’m very aware that I need Gerald on my side to get what I want from him. In that moment, Gerald has a degree of power over me. The result of this power imbalance is that I choose to act in a different way to how I would actually like to act.

Similarly, I imagine, Gerald wants to keep his job. Gerald may be thinking what a demanding and annoying customer, and in an ideal world may want to tell me “where to go”. But Gerald needs his job. Gerald needs his rent and food money. Gerald acts as politely as possible because he knows this call is being recorded, his manager could be listening, and he does not want another complaint about him. I have a degree of power over Gerald. The result of this power imbalance is that Gerald chooses to act in a different way to how he would actually like to act.

Get where I’m going with this?

Power dynamics play a role in almost all of our relationships. With our brother or sister, a manager, the waiter in a café we frequent, and the service user we are supporting.

As we gain more power, we use it. That’s widely evidenced (check out some interesting reads about power dynamics at the end of this blog). And using power isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Having lots of power does not necessarily corrupt, but it heightens our pre-existing values and ethical tendencies. As people become more powerful, they often believe their values and ethics are correct and then begin to use that power to foist their values and ethics to those around them.

If I had complete power over Gerald, I would be exerting mybelief (or value) that I deserve a cheap contract, with extra perks because I am a loyal customer, and I would use that power to make sure that Gerald realises and does what I say. Our values will also often lead us to think “I am right”, “I have better values than you”, and “you should follow my values”.

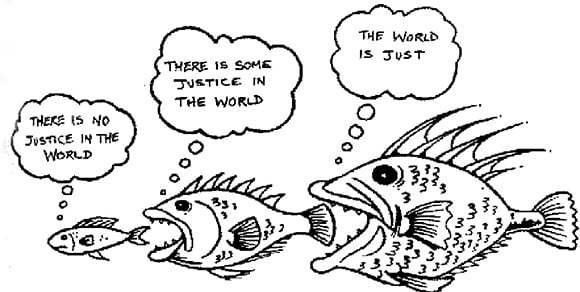

Think about the cartoon below. The largest fish is fat and plump and healthy because it eats and devours the smaller less powerful fish. It has power. And because it is healthy and happy it believes the world is a fantastic place, that ethically it is the right decision, and it makes these decisions based on its ethics and values.

So how do we use power correctly? How do we balance self-interest against the common good?

Imagine supporting a service user. Imagine how much they might need you or the service you provide. When we’re offering support, we’re offering shelter, sometimes funds and food. Imagine what they would do to get and retain this support. Imagine how much power we, as a support worker, as an organisation, would hold over them. Imagine the dance we would inadvertently take part in.

I have what you need. What will you do to get it?

At Second Step we believe in collaboration and coproduction and we are improving this every day; and it’s a journey. Power always has to be checked, considered and where possible re-distributed.

Some of the things we can ask ourselves in order to prevent a power imbalance are:

Who are you?

- Genuinely take some time to reflect on what power you hold; what is your role? Who do you manage? Who do you support? What is your degree of control over someone else?

Do you need the power?

- If you have power, where and when can you let go of it? If you are in senior management, are there forums in which you can be more equal and not use your authority?

- If you are a support worker, do you need to make a decision or can you let the service user make this decision for you (providing it is safe to do so)?

What values underpin your power?

- When making decisions, particularly decisions that affect the actions of others, think about your values and your ethical motives. Why is it important to you that this particular course of action is taken? Have you considered the impact on everyone else’s values? Do you recognise that people do not have the same values as you?

Do you have something someone else wants or needs?

- Always pay attention to what it is someone really wants or needs from you. Does this need and reliance on you put you in a position of power? How might you give this power back to this person? Will a decision you make stop them getting what they need? Could the power imbalance force this person to act in particular ways in order to get what they want?

Articles on Power Dynamics

https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/collections/201802/the-power-dynamic

(https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/why-power-corrupts-37165345/)