Waking up to the realities of Bristol’s past

To mark this year’s Black History Month, Second Step Internal Comms Officer Josie shares her thoughts and feelings after joining a walking tour and talk based on the recently released book Breaking the Dead Silence: Engaging with Legacies of Empire and Slave-Ownership in Bath and Bristol’s Memoryscapes.

On Wednesday 15 October, I joined academics and authors Rob Collin, Mark Steeds, Dr Richard White and Dr Christina Horvath on a walking tour across Bristol, engaging with the city’s legacy of colonialism, empire and slavery.

Based around the recently published book Breaking the Dead Silence: Engaging with Legacies of Empire and Slave-Ownership in Bath and Bristol’s Memoryscapes, a number of the authors who contributed to the book ran an afternoon walking tour of Bristol, followed by a book launch and readings in the evening.

As Second Step is a Bristol-based charity it feels important to engage with Black History Month events across the city. The book’s launch was planned for October to coincide with this year’s theme, Reclaiming Narratives.

The book itself is a collection of diverse voices reflecting on the toppling of Bristol’s Colston statue and the Black Lives Matter movement. Through critical commentaries and personal accounts, the book includes perspectives from academics, artists, activists, heritage professionals and tour guides.

I felt the walk and book launch conversation have helped me see Bristol through new eyes – it was a meaningful way to engage with the cities challenging history. Despite its modern progressive reputation, I was shocked by how little has been done to acknowledge the unimaginable harm inflicted by the transatlantic slave trade which had bought so much wealth to Bristol; wealth which the south-west arguably still benefits from now.

What is a memoryscape?

A memoryscape is a way of describing a remembered landscape, in this case the collective memory of Bristol and Bath.

There are two memoryscapes associated with these cities – one is the ‘official’ memoryscape, or the memories that the establishment have chosen to remember and acknowledge, while the other is the memories that don’t fit the official narrative. These unofficial memories may be found in ‘clues’ around the city. For example, the smashed paving slab where the statue of Colston hit the ground during the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020.

The crack in the pavement where the statue hit the ground

That Bristol was an active trading port with a strong seafaring history is celebrated in the official memoryscape – with the SS Great Britain and replica Matthew ships on display as tourist sites. However, the official memoryscape barely acknowledges Bristol’s role in enabling colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade in the 17th and 18th centuries.

This is especially shocking considering Bristol was the leading English port at that time and was the place where half a million people were bought and sold.

A lack of remembrance

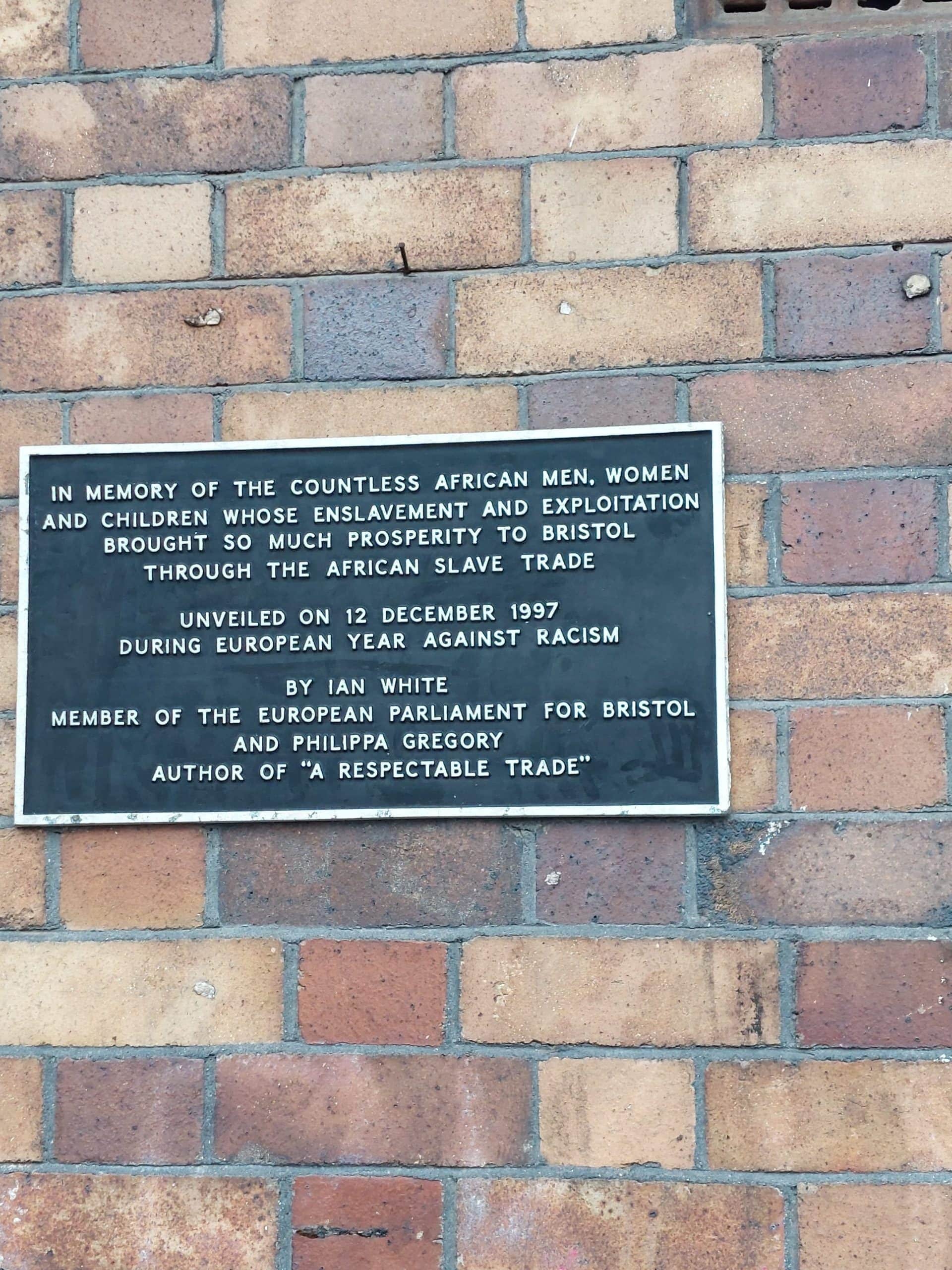

There is minimal acknowledgment of the vast scale of human suffering in Bristol’s iconic harbour. A small plaque outside M Shed reads:

“In memory of the countless African men, women and children whose enslavement and exploitation brought so much prosperity to Bristol through the African slave trade.”

The easy-to-miss plaque outside M Shed

Another easy-to-miss acknowledgement of the city’s history is Pero’s Bridge – the footbridge spanning the floating harbour with two distinctive horn-shaped sculptures.

As explained by a small, dark sign at ankle-height, the bridge is named after Pero Jones who was enslaved at just 12 years old when he was bought by wealthy enslaver, plantation owner and sugar merchant John Pinney. The Pinney family moved to Bristol in 1784, bringing Pero with them.

The plaque (pictured above) beside Pero’s bridge (pictured below) is almost illegible

Dr. Richard White, who co-authored and edited the book and led the walking tour, uses his work as a walking artist-researcher to explore history through untold or obscured stories with a look towards social justice. Explaining his work further, he said:

“It is my view that to be part of the constructed amnesia and the forgetting of injustice is to become complicit in its persistence. Racism and its inverse – white supremacism – became structural through the transatlantic trade and European colonialism. My view, as a white man, is that without reaching back to and owning that past we remain shackled to it. Making a way, walking and asking questions, I attend to complicity and white privilege; I seek to become more alert.” Breaking the Dead Silence launch – Bath Spa University

By writing Breaking the Dead Silence, the authors and editors offered multiple perspectives from academics, artists, activists and heritage professionals – contributing ideas and strategies towards re-telling obscured stories and getting unheard voices heard.

Ripples still felt today

It feels important to acknowledge that Bristol and Bath both continue to benefit from the wealth generated by the transatlantic slave trade today. As discussed in the book, Bath’s stunning Georgian architecture was largely built from the profits coming out of Bristol’s port. It’s these buildings which are such an attraction for tourists visiting the city today – and it’s estimated tourists bring nearly £500 million into the local economy each year.

Pulteney Bridge, Bath – named after Frances Pulteney, wife of slave plantation owner William Pulteney

For further information on Bath’s role in the transatlantic slave trade, it’s well worth joining author Rob Collin on a walking tour of the city where he discusses the cities slave economy during the 18th century. Rob Collin Guide | Guided Tours in Bristol and Bath

Another jaw-dropping fact is that following the abolition of the trade in 1834 slave owners were paid £20 million in reparations for the loss of their slaves – an amount is equivalent to £17 billion today. The debt incurred from paying these reparations was paid off by the British taxpayer, with the debt only clearing in 2015. Anyone paying taxes in the UK before this date would have been contributing to clearing this debt.

In summary

The book launch and walk were eye-opening experiences, forcing the audience and participants to consider their own relationship with the city and its colonial past.

Despite having walked past the spot hundreds of times, I’d never noticed the crack in the pavement where the Colston statue fell and now will take the time to acknowledge and remember the long chain of events leading up to that moment whenever I pass by. I’m hopeful that seeking out the city’s painful history and engaging with the strong emotions it evokes will ensure this history of suffering won’t be forgotten or repeated.

Engaging with and understanding Bristol and Bath’s colonial legacy is a way to address the difficult past of both cities and how it overlaps and juxtaposes with the present.

A free PDF of Breaking the Dead Silence: Engaging with Legacies of Empire and Slave-Ownership in Bath and Bristol’s Memoryscapes has been made available by the authors here: Breaking the Dead Silence | Home